Culture, Ideology and the Work of Social Movements

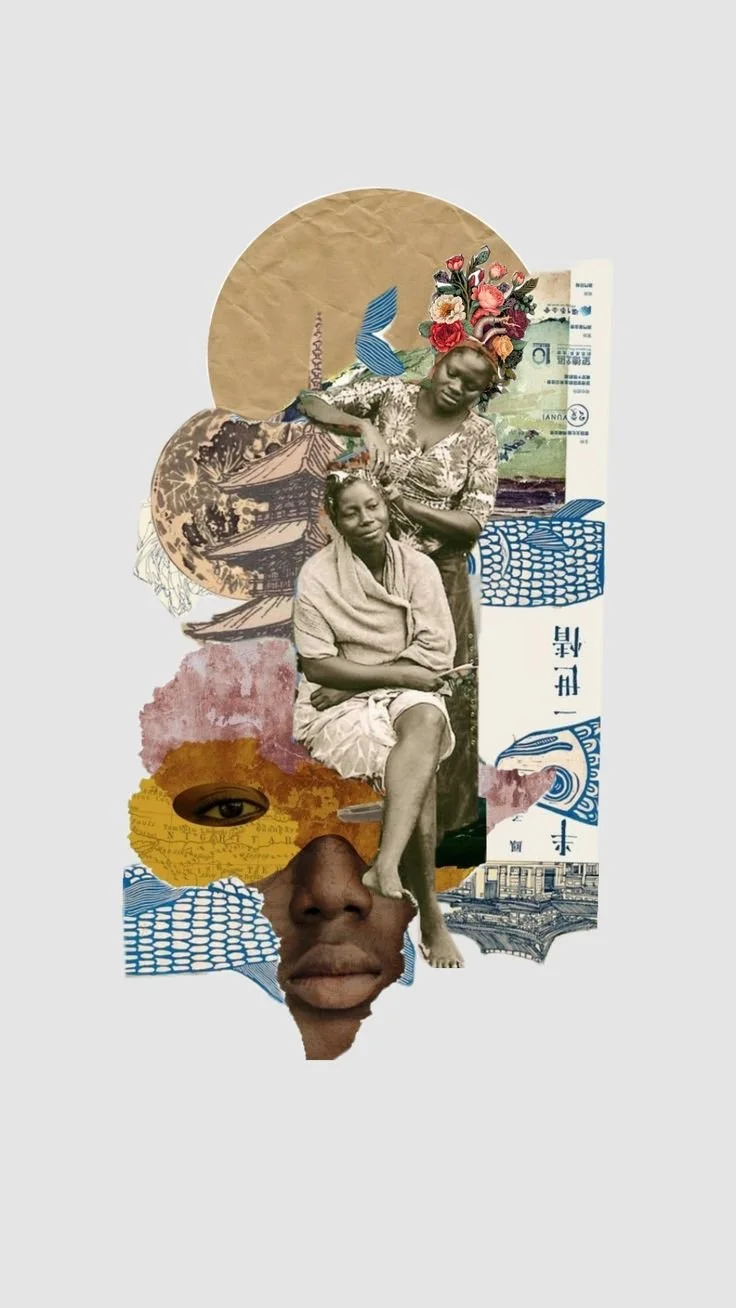

Summary. This blog argues that achieving social justice means more than passing better laws or persuading individuals; it requires transforming the cultural “toolkits” that make unjust arrangements feel natural, necessary or even good. Drawing on Sally Haslanger’s account of ideology as ‘culture gone wrong’, it shows how entrenched social meanings shape what we can see, feel and value, and how they help reproduce racial, gendered and economic hierarchies even after formal reforms. The piece makes the case that social movements are indispensable culture‑makers: they expose hidden harms, develop new concepts and identities, and experiment with alternative ways of living that reconfigure what counts as reasonable or possible. For organisations and practitioners, the core challenge becomes not only “What should we advocate in policy?” but “Which cultural technē are we reinforcing—and which counter‑practices and narratives are we willing to help build?”.

Achieving social justice is not only about better laws or kinder individuals; it also demands transforming the culture that makes injustice seem normal, inevitable, or even valuable. Haslanger’s central claim is that unless we challenge and remake the shared meanings that organize our lives—our cultural “toolkits”—legal reforms and personal goodwill will repeatedly fall short.

From “bad people” and “bad laws” to “bad cultural tools”

Haslanger distinguishes between repressive injustice (forced upon individuals through coercive measures) and ideological injustice, where people—often including the subordinated—unthinkingly participate in oppressive practices because they seem natural, right or necessary. In ideological oppression, the problem is not simply ignorance or malice at the level of individuals, but a background cultural “technē”: a network of meanings, norms, habits and interpretive tools that shape what we see, feel and treat as important.

On this view, culture is not decoration around politics or economics; it is a semiotic infrastructure that structures how all of those domains are lived. It provides shared repertoires—habits, skills, scripts and styles—from which people build their “strategies of action” including how they make sense of race, gender, class and other social positions.

Why law and policy are not enough

The history of school desegregation in the US is exemplary: Brown v. Board of Education declared segregation unjust, but decades later many districts remain effectively segregated and racialized inequalities in education persist or have worsened. White flight, gerrymandered school zones, and the slow dismantling of desegregation orders all reveal a cultural-technē that continues to code Black communities as disposable and white advantage as normal or deserved.

This looping between meanings and material structures matters: cultural schemas shape how resources (schools, housing, safety, opportunity) are produced and distributed, and those unequal distributions then appear to confirm the original cultural narratives. What emerges is not a single “bad belief” but a resilient structure in which social meanings, institutions and lived spaces mutually stabilise injustice and make it look like common sense.

Ideology as culture gone wrong

Haslanger defines ideology as culture “gone wrong”: a cultural technē that organises us around distorted understandings of what and who matters, and thereby stabilises unjust power. Ideology produces both epistemic wrongs (we systematically misperceive or misinterpret morally relevant facts) and political wrongs (we are organized into unequal, harmful structures).

Crucially, ideology often works by filtering what we can see at all. For example, racialised and gendered schemas shape perception, so that Black people are “just seen” as dangerous or unreliable, or poor women’s experiences in maternity care are treated as noise rather than as claims of right. Under ideological conditions, even conscientious agents exercising “good” reasoning within a given cultural toolkit can fail to recognize injustice, because the available meanings themselves are flawed.

Moral knowledge from within struggle

If culture shapes values and reasoning, how can we ever step outside it to critique? Haslanger’s answer is not to appeal to abstract ideal theory, but to non‑ideal moral epistemology grounded in social struggle. Oppression is often first named and understood from within: by those who experience harms in their own lives and relationships, and by movements that consolidate those experiences into shared claims and demands.

On this account, there is real (if fallible) moral knowledge: we can know that specific practices and structures—such as slavery, segregation or gendered violence—are wrong, even if we lack a complete theory of justice. Critical theory’s task is then to take these situated insights seriously, elaborate them, connect them to empirical realities, and identify the cultural technē that makes such harms seem acceptable or invisible.

Why social movements are culture-makers

For Haslanger, the practical answer to—How do we achieve social justice? and How do we change society for the better?—is: by building and sustaining social movements that can contest and transform culture, not just law. Movements are crucial because they:

Create counter-meanings, counter-identities and counter-practices that reveal existing injustice and prefigure more just forms of life.

Accumulate credibility and power through collective resistance, making it harder for dominant institutions to ignore or suppress demands.

Offer new cultural tools—concepts (like “sexual harassment” or “Black Lives Matter”), narratives, rituals and norms—that people can inhabit and use to reorganise everyday practices.

From this perspective, philosophy and critical theory are not spectators but participants in culture-making: they help articulate the wrongs, map the structures and sharpen the tools that movements need to reconfigure what counts as thinkable, sayable and doable.

For strat4, the implication is sharp: if we are serious about social justice, our work cannot only advise on policy tweaks or individual behaviour change—it must help clients and collaborators disrupt harmful cultural technai and cultivate alternative repertoires that support more just and livable worlds.

If we take Haslanger seriously, then “business as usual but nicer” is not an option. We need to get deliberate about the cultural technē we are reproducing—and the counter‑cultures we are willing to nurture.

For strat4’s community, that means:

Treat every project, campaign and workshop as a site of culture‑making, not just message delivery.

Centre the concepts, experiences and leadership that emerge from movements and communities on the sharp end of injustice, and let their insights reshape your brief—not just your language.

Audit your own organisational habits: which stories, identities and assumptions do they normalise, and whose realities do they erase or pathologise?

Invest in practices (forums, experiments, coalitions) that help people rehearse different ways of relating—more equal, more accountable, more livable—so that alternatives to the status quo become thinkable and doable.

The invitation is simple and demanding: stop asking only “What should we say about justice?” and start asking “How can we join with others to transform the cultural tools that decide who and what counts?”